Virginia Cavalier’s Pack Line Defense

What is the pack line defense?

Pack line defense is a popular man-to-man defense run at all levels that was popularized by Dick Bennett while he was the head coach at the University of Wisconsin. Pack line emphasizes taking away dribble drives and interior scoring options, while forcing teams to settle for and beat you with outside shots.

Throughout the years it has been copied, adapted and modified by coaches at all levels but one thing is common across all versions of the pack line defense—while it is a man-to-man defense, it is not an individual defense. All five defenders must be on the same page, communicating and in proper position in order to effectively play this defense.

While Dick Bennett and the University of Wisconsin popularized the defense, his son Tony Bennett and the University of Virginia have made it a staple of today’s college basketball landscape. Hundreds of teams across Division I play the pack line defense, but none better than the Virginia Cavaliers. In this breakdown, we will dive deep into the basic concepts and principals of Virginia’s pack line defense.

Pack line Basics:

Pack line defense is based around funneling the ball into help, taking away dribble penetration and forcing teams to score from the perimeter. The reason it works so well in today’s game, especially at the high school and college levels, is because today’s offensive players are better ball handlers than they were 20 years ago, but much worse without the ball in their hands.

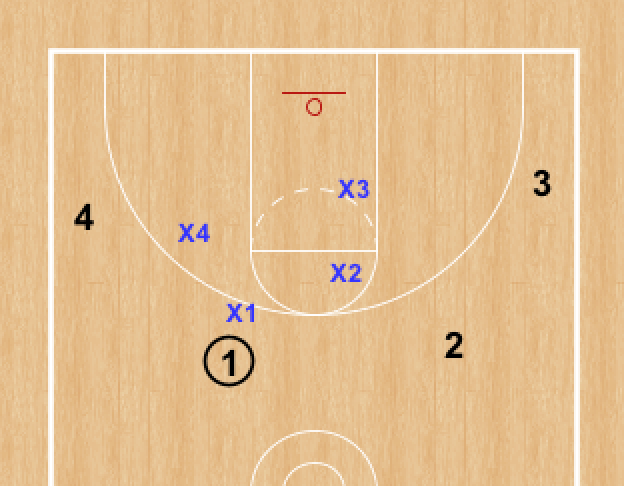

The basic keys to emphasize when implementing or coaching pack line defense is aggressive ball pressure and smart positioning from the off-ball defenders. If a defender’s man does not have the ball, he should have two feet in the “pack line.” The pack line is an imaginary line 16-17 feet from the basket (1 step in from the three point line) that mirrors the three point arc all the way around.

Defending the Ball in pack line:

Despite the misconception that pack line is a non-pressure defense, that simply isn’t the case. The on-ball defender needs to play with extreme ball pressure, knowing he has help behind him. Beyond pressuring the ball, the on-ball defender has one additional job—never get beat baseline. Pack line defense is designed to handle and neutralize dribble drives to the middle of the floor. However, the one thing that will kill a pack line defense over and over again, is the baseline drive.

In addition, the on-ball defender can never give up a straight line drive to the rim (i.e. from a poor closeout). There is not a single defensive scheme in existence designed to handle straight line drives.

Defending the Perimeter in pack line:

If your man does not have the ball, the general rule of thumb is that you have two feet inside the pack line. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule—for instance if your man sprints to set a ball screen (Virginia hard hedges ball screens, which we will cover later).

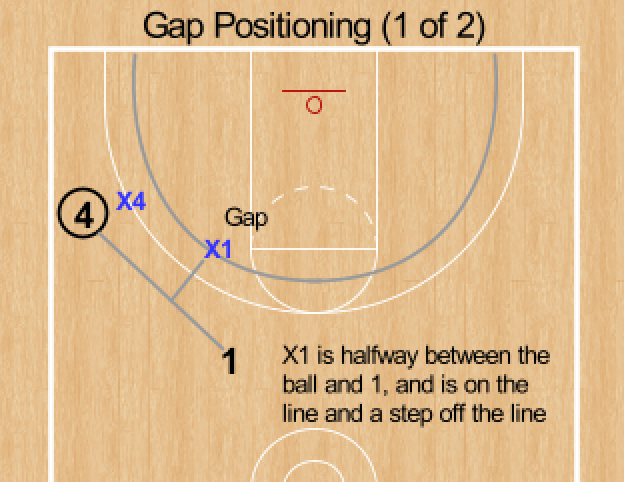

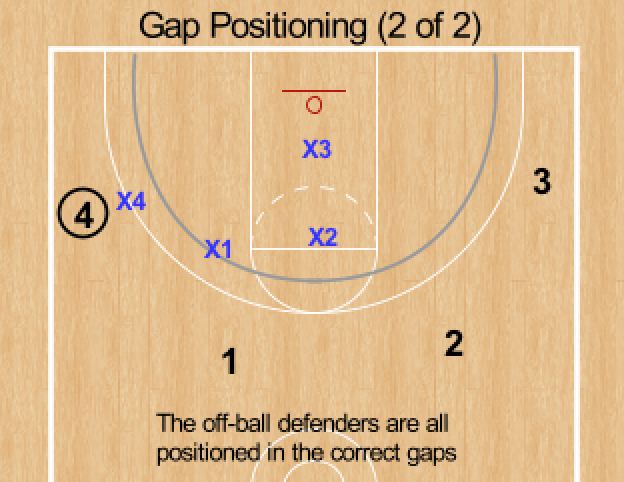

The off-ball defenders should be halfway between the ball and their man, and they should be on the line and a step off the line that would connect the ball to their man. This imaginary line connecting the ball to the defender’s man applies to all areas of the court outside of the post. This line will constantly change and shift with offensive player movement, but no matter what the off-ball defenders are always on that line and a step off the line.

This positioning is now as “gap” and is the basis of the pack line defense. By positioning in the gap, the off-ball defenders are already in perfect help position on a potential drive. Rather than having to help and then recover, gap positioning allows a defender to simply recover as they are already positioned to help.

Each time the ball is passed along the perimeter, the off-ball defenders find themselves in one of two scenarios:

The ball is being passed to the player they are guarding

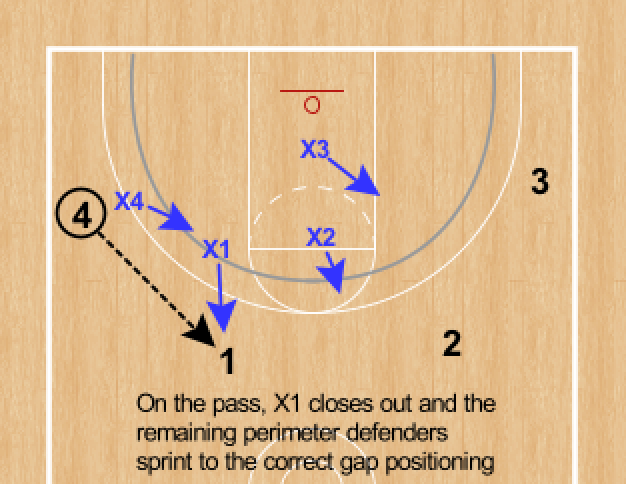

If the ball is being passed to the player they are guarding, the defender must first “move on air.” This means the instant the ball leaves the passer’s hands, the defender is closing out to his man with high active hands and he becomes the on-ball defender. Moving on air is a non-negotiable for all five defensive players—as the ball is in the air, all five players are moving to their correct positioning on “air time.”

The ball is not being passed to the player they are guarding

If the ball is not being passed to the player they are guarding, the defender must once again move on air. But rather than closing out to the new ball handler, they will sprint to the correct gap positioning (on the line and a step off the line).

If all five players follow the above techniques and rules, the entire defense will have been shifted and correctly positioned by the time the pass is received and the next action begins.

Closeouts:

Perhaps the biggest fundamental of perimeter defense within pack line is closing out on shooters. With pack line defense being designed to take away interior scoring options, theoretically the only option left for the offense is to take shots from the perimeter so guarding and contesting outside looks is key to any successful pack line defense.

Virginia coaches their players to begin closing out on a sprint and finish with short choppy steps. As the ball is kicked to a shooter or perimeter player, the defender responsible for the shooter is moving on air and sprinting to close the distance. As he begins to close in on the shooter, the defender begins to chop their feet to regain balance and arrive on the ball in an athletic position so they don’t get beat on an immediate drive.

Virginia also coaches their players to close out with two high hands—the reason for this is it discourages shots in rhythm, limits quick passes over the top, and takes away the offensive player’s vision. The two high hands of the closeout actually occur simultaneously with the short choppy steps. As the close out defender begins to break down and chop their feet, they sink their hips and throw both hands in the air as the player is receiving the pass.

Defending the Post in pack line:

When defending the post in pack line, and really all defensive schemes for that matter, the work must be done early. What I mean is the post defender has to fight for position early and often. If you wait to begin fighting for position once the ball has been entered into the post, it’s too late. The post defender should use a clenched-fist arm bar to fight for position early and push his man outside of the post box (see image below)—the goal is no two-footed catches inside the post box. Anytime the offensive post player does not have the ball, the post defender must constantly be battling for space.

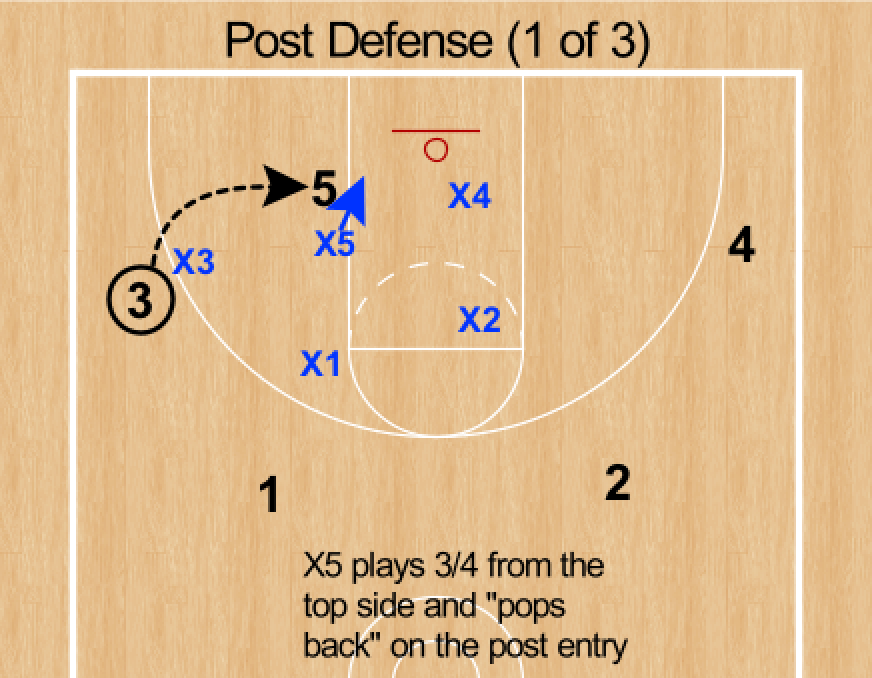

The general rule of thumb for the post defender is to be positioned 3/4 on the high side of the post player, and they can never allow a post entry from the top (high-low). The only time you don’t look to play 3/4 from the high side is when the post player flashes to the elbow or free throw line. This positioning, combined with the perimeter defenders not getting beat baseline, eliminates the most common post entry passing lanes and keeps the offensive player from catching the ball deep.

If the ball is entered into the post, the post defender immediately “pops back” or jumps from 3/4 to playing directly behind the post player. The post defender should pop back while the pass is still in the air, so the post defender has no initial advantage on the catch. Once the post player has the ball and the post defender has popped back, he should wall up and show the referee his hands. If the post player attempts a shot, stay on your feet with your hands high and walk into the shooter (foul him with your hips).

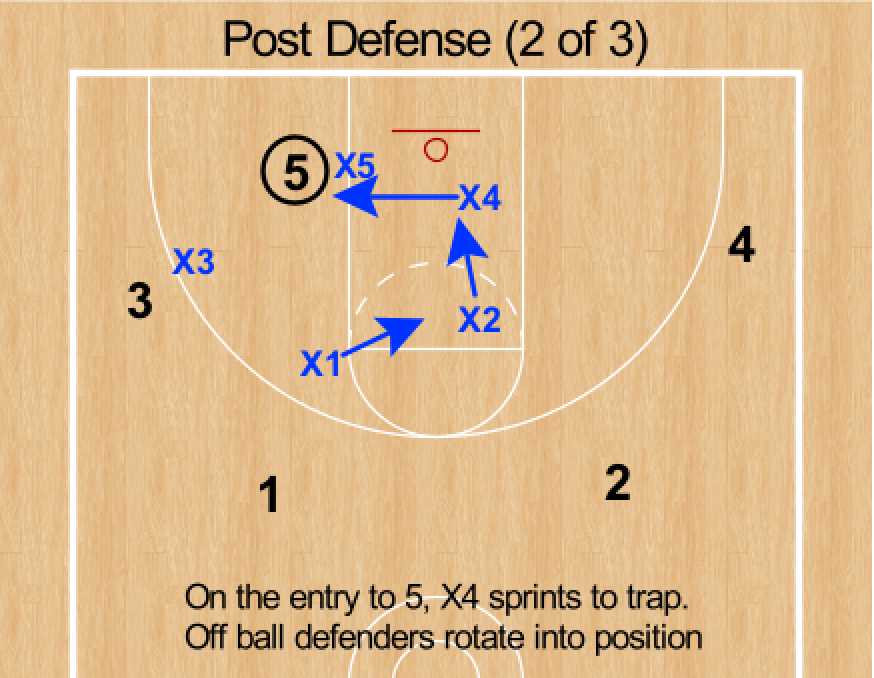

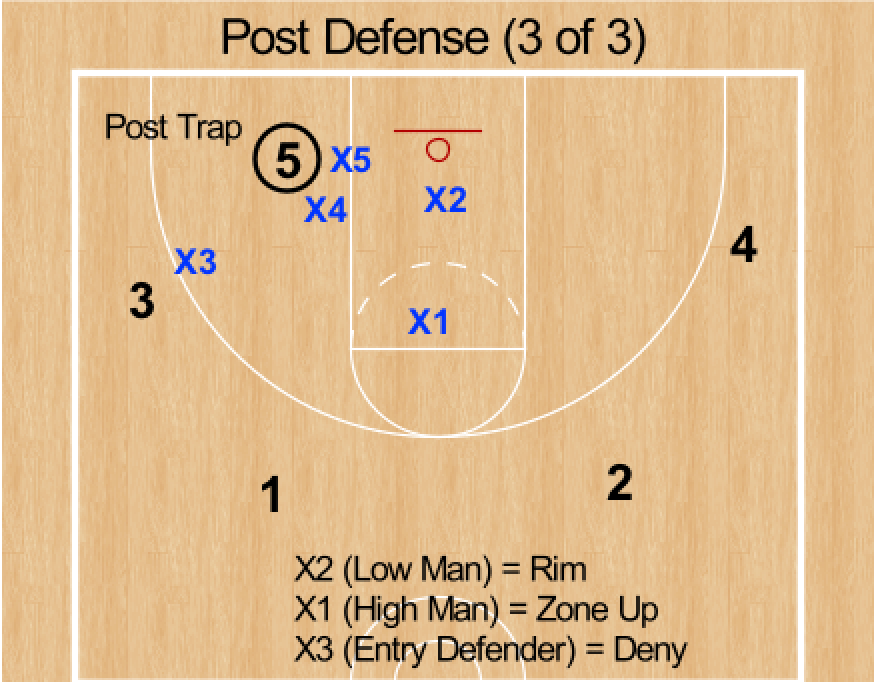

When the ball is entered into the post, Virginia immediately sends the opposite big (X4) to double and trap the post. X4 must sprint to double as the ball is still in the air or on “air time.” The defender guarding the player who made the post entry (X3) will deny his man once the post entry is made. This eliminates the easiest outlet for 5 to escape the trap. The lowest off ball defender X2, will sprint to the rim and protect against any cutters. The final off ball defender will “zone” up and be prepared to close out on a cross court skip pass. Once 5 breaks the trap or retreats, X4 sprints to recover back to his man, while the off ball defenders do the same.

Defending Ball Screens:

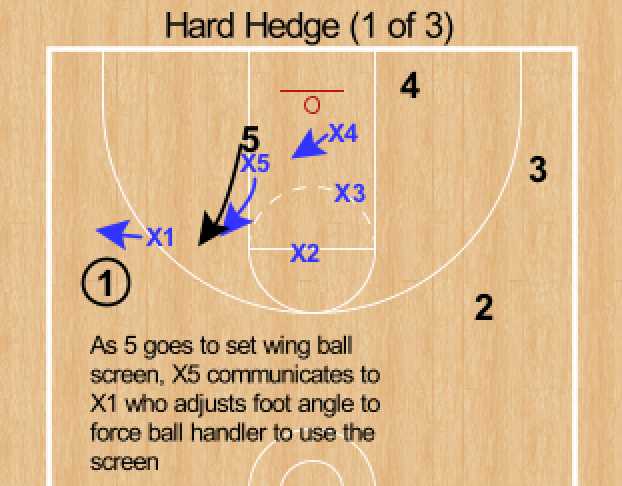

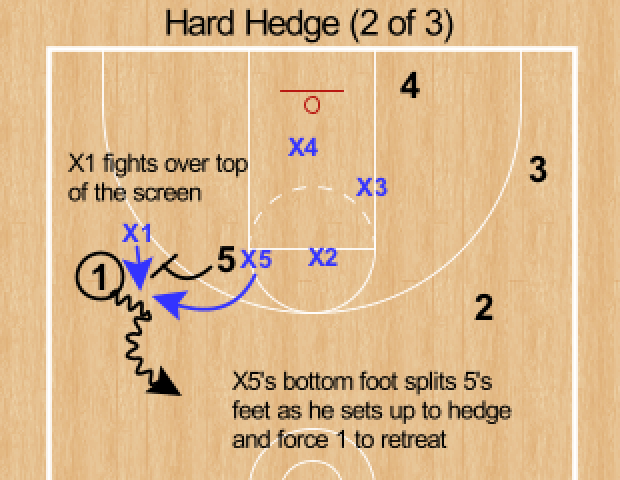

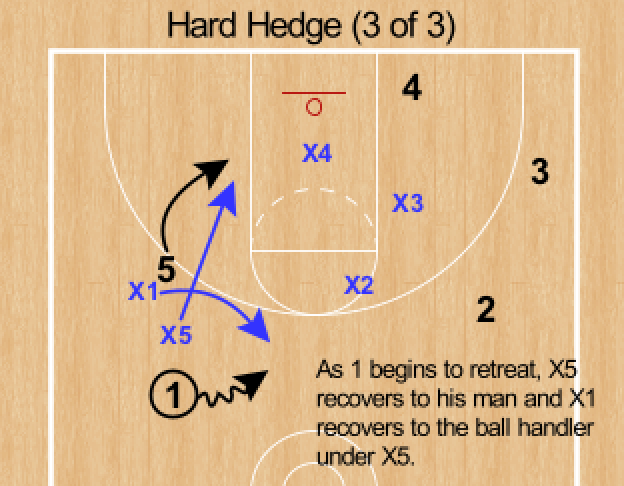

Virginia famously defends ball screens in their pack line defense by hard hedging, and they do this especially well. As the ball screen is being set, the screener’s defender gets in the ball handler’s path as he comes off the screen with his shoulders facing the ball handler (parallel to the sideline). The screener’s defender’s goal is to force the ball handler to slow his momentum and retreat, ideally towards half court.

As this is happening, the defender who was guarding the ball fights over the top of the screen and goes under the screener’s defender as he hedges out. The screener’s defender then sprints with high hands to recover back to his original man, the screener. The opposite big not involved in the ball screen action is tasked with “helping the hedger” if needed, and rotating to cover the screener if he rolls to the rim.

To learn more about hard hedging ball screens, check out the Ball Screen Defense—Hard Hedging Ball Screens breakdown here.

Defending Away Screens:

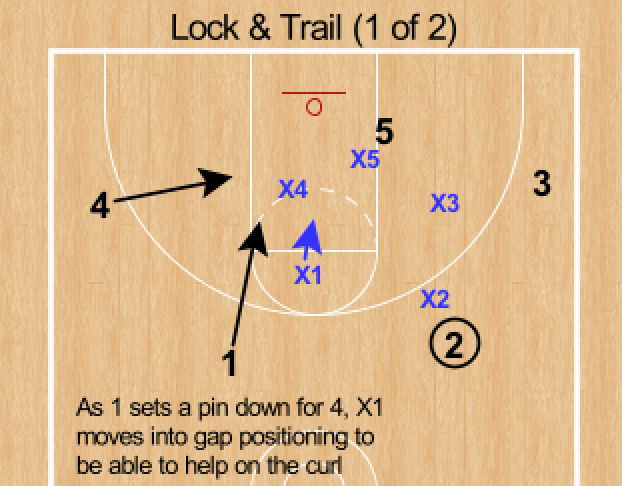

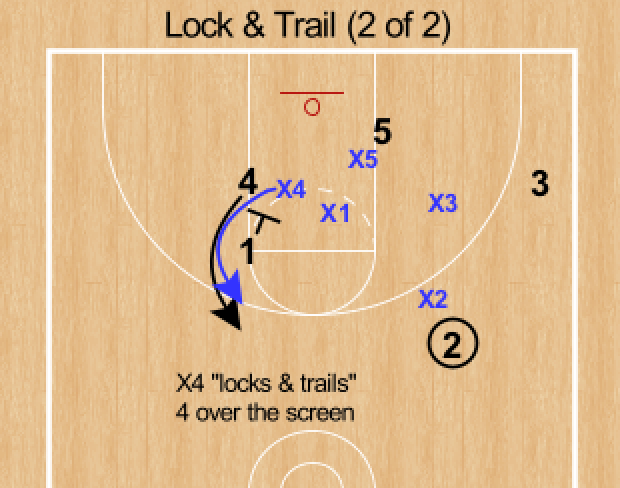

To defend away or off-ball screens, Virginia uses the “lock and trail” concept. The defender guarding the player coming off the away screen, will lock onto the offensive player’s near-side hip and trails him over the top of the screen.

The screener’s defender sags in gap position to help on a potential curl cut from the offensive player. The curl is often a hard cut and pass to connect on, especially since the on-ball defender making to look the pass is playing with extreme ball pressure. Once the lock and trail defender has recovered on the now ball handler, the screener’s defender recovers back to his man.